“Not everyone is on the same level,” sophomore Maddy Schosha said. “Different people need different things.” Recently, during a listening session at the Greater Albany Public Schools district office, there was a discussion of detracking math where students K-7th will all be learning the same content at the same time. This limits the opportunities for students to take classes that better suit their educational needs, “some different people are at different levels, and no one should have to feel like they’re not allowed to be at the level,” Schosha said.

The phrase detracking means that students will be detracted from their educational needs and will be put on a tracked path by schools. Being tracked means everyone is learning the same content at the same time. There are many theories on how detracking will be implemented. According to Sam Hartman, during a meeting with the Oregon Department of Education, the math curriculum would be changed, and every freshman would take Algebra I and Geometry, then break them off into separate pathways.

“One pathway is to take an integrated course—it’s basically one year of both Algebra I or Algebra II and Precalculus combined,” Math teacher Sam Hartman said. Merging Algebra II and Precalculus is the state’s current plan to get every student to high school with a possible pathway to Calculus in high school.”

One of the main goals of detracking is to ensure that all students can reach Calculus without having to be pushed ahead, whether that is taking Algebra I in seventh or eighth grade or being able to take Algebra I as a freshman and still reach Calculus without having to double up on math classes.

The Corvallis School District has detracted its math curriculum. Many classes are being removed because they are no longer obtainable or practical for students because of the rigorous pace required in class.

“Calculus BC is something that I created at Crescent Valley [High School],” Advanced Mathematics instructor Paul Buchanan said. “That class will exist for one more year, and then it’s gone.”

Many students in the past have been given the opportunity to be on an advanced path in mathematics by taking Algebra I in seventh grade, which has allowed them to pursue other math courses such as AP Calculus AB and AP Calculus BC. However, it wasn’t by chance that students got the chance to get ahead. It was often recommended by teachers and parents advocating for their children that they needed a more stimulating and rigorous education. Teachers have been able to identify certain students who appeared to be bored in class and would complete work faster than others because they were able to process the content quickly.

“In sixth grade, I went up to my teacher and asked, ‘Can I be in seventh-grade math?’ ‘She said, ‘ You have to do these, ‘ and she gave me probably about 15 assignments,” Sophomore Jakob Ylen said.

“I had to complete that math by the end of that week.”

In some cases, students advocate for themselves, much like Ylen, to take a challenging course at such a young age. However, Schosa said, “I did have my teacher at the time, who recommended that I be allowed to do [advanced math]. And if she hadn’t recommended me, I wouldn’t have been allowed to if she’d said no.”

However, in some cases, students who are placed on the advanced path may find themselves struggling as they get to Calculus because they learned the content so quickly.

“Sometimes the student gets accelerated, and then maybe they pass the class but don’t really have all the skills well developed. Maybe they get accelerated, but then they get a C in Algebra one, so they move on and get a C in Geometry, move on. They’re not really solving those skills.” Hartman said. In mathematics, every concept builds on one another, and pushing a student ahead before they are truly ready may cause problems for them in the future.

“I feel like [younger students] haven’t really grasped the depth of everything they’re doing,” Buchanan said. “They focused on getting an answer, and they really haven’t appreciated all the other ins and outs of what’s happening with math.”

Although Ylen said, “The benefit is the kids will be pushing themselves.”

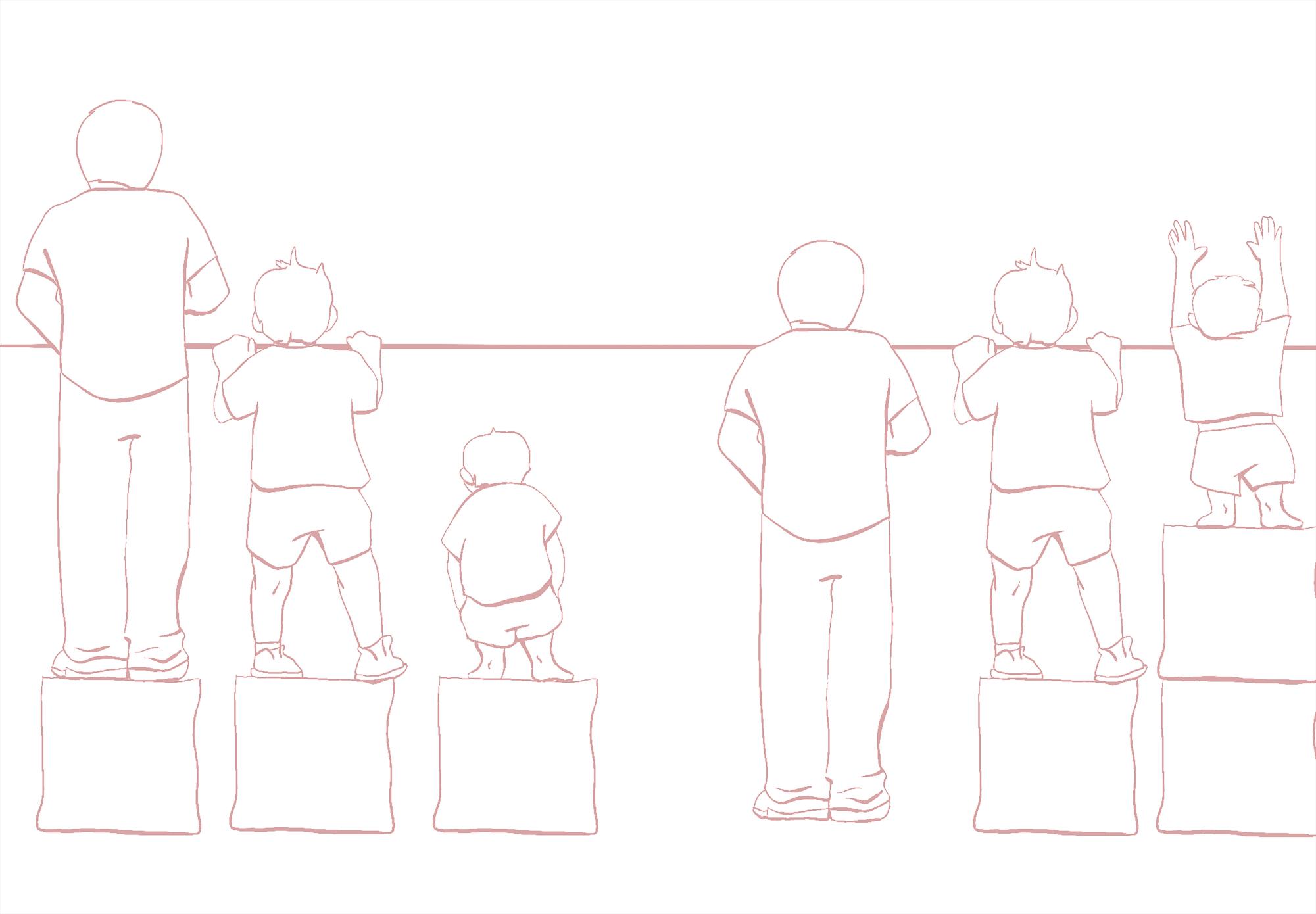

One benefit of detracting math is reducing the equity gap. The equity gap is the performance levels between the lowest-achieving student and the highest-achieving student. Detracting math will reduce that gap, making things equitable for all students.

However, when students aren’t learning what they need in class, the subject starts to get boring. “Being adequately challenged to continue learning is a really important thing for students,”Hartman said.

“Not giving that opportunity to some students. Math starts to get boring.” Hartman said.

“[Students] should have the chance to prove themselves and show how developed their mind is. And if they don’t, it’ll be harder for them in the future to stay on track because they’re just going to be completely bored out of their minds.” Ylen said.

“I feel like when it comes to advocating for these kinds of things, at the end of the day, I’m not just advocating for myself alone, “Schosha said. “There’s this group of other people who benefit from this sort of thing, and to deny everyone this opportunity because it doesn’t work for everyone seems silly to me.”