Everyone recognizes the posters depicting Uncle Sam aggressively pointing at the viewer, “I WANT YOU” in capital blue letters at the top. The last significant uptick in people enlisting in the military was between 1964 and 1973, during the Vietnam War, where a third of the serving men were drafted. Active personnel reached over 3.5 million before the war grew too, according to the website History in Pieces.

However, this isn’t the 1960s. Modern problems require modern solutions.

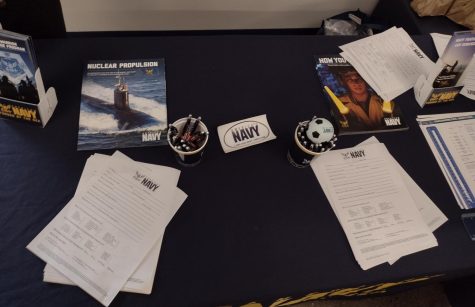

During school registration, there were papers taped around the school telling juniors and seniors to fill out a Google Form if they didn’t want to be contacted by the military. Even so, military personnel are still allowed an opportunity on campus. If college representatives are allowed to send little green slips of paper to students to inform them of a meeting, military recruiters are allowed the same access, per federal law. But instead of handing out flyers, recruiters post themselves in the lobby with a table containing free pens, informational papers, and a nice uniform.

In the Career Center, Lynn Magnuson schedules the recruiters to visit during lunch, but school administrators have the authority to decide who can arrive and the designated area for them to occupy.

Since the official draft was abolished in 1973, enlistment has relied on voluntary commitment. In the past, rumors that recruiters purposefully went to low-income high schools and tried to sell them on joining. With benefits such as health care, housing, job training, and life insurance after retiring, high school graduates with limited options might not see easier courses. Or children of immigrant families might see the opportunity of education programs to ensure their future financial stability. Similar to the draft from the 1960s in that those wealthy enough were able to afford higher education, but the working class had little option.

Strangely, the U.S. Army based in Kentucky had a Twitch account in 2020 where they gave away prizes and links that sent viewers directly to the Army recruitment form. Twitch flagged them when the Army and Navy esports teams started banning viewers who pointedly asked about war crimes, which Twitch said was a violation of the First Amendment. And while the Army banned the use of TikTok on government phones in 2019, some still used the app to bribe people to join.

That’s not to say recruiters should be locked out of school. People’s actions can give their organizations a bad reputation, but that doesn’t mean everyone should be seen or treated the same way, especially if they actually perform ethically. The approach the military takes to present themselves at the school is quite commendable. Compared to colleges that send piles of emails, or spam callers that are so common that people made apps to combat them, the military is ironically docile. Their presence at this school is the opposite of aggressive as they stand casually and wait for students to approach the table on their own. After that, recruiters such as PO1 Nicolas G. Ensign are more than happy to answer any questions thrown their way. Or, in Ensign’s case, prompt kids to ask questions about his sleeve tattoo on his left arm.

“When I was 17, I had no guidance in my life, and I wanted to travel. That’s why I joined the Navy,” Ensign said. “I want to help kids figure that out as well.” He estimated that 30 to 50 kids ask them questions each visit, and about five people decide to sign up to join the Navy afterward.

Ensign said that being a recruiter is voluntary for three years, and those interested sign up in the initial contract with the Navy. From there, they’re assigned schools to visit based on the job they chose. Creating good relationships with the school is key, so any form of aggression to students is not the way to remain in good graces of administration, nor is that good for any form of reputation building.

“I care about finding leaders, and leaders can come from low income schools like I did, or rich schools who pay a lot of money for [stuff],” Ensign said with a wave of his leather watch-bound wrist. “You find those people everywhere. It doesn’t matter what school it is.”

Someone should raise their hand to take that oath because they genuinely want to and because they have all the information possible. Being able to ask someone millions of questions because one’s confused about life after high school shouldn’t be condemned, it should be normalized just as much as talking to people in other professions. It’s a method of reaching out that other businesses and occupations don’t use, and it shows the military’s willingness to listen, to help, and to make people feel welcome.