Walking into the leadership classroom for the first time since the pandemic, senior and student body president Sid Holloway was looking forward to seeing the smiling eyes of her peers and working to improve the school as a tightly-knit team. Unexpectedly, that wasn’t the scene she was greeted with. Before school transitioned to fully virtual, Holloway recalled, leadership was a very “interconnected” class, with committees of students all working toward their respective goals. An environment that fostered mutual respect and appreciation. That camaraderie isn’t completely absent now, but there’s something holding it back from reaching the same level.

“We’d go into our big committee room and we’d be trying to brainstorm,” Holloway said, “and I’d look around, and half our committee would be on their phones.”

As the year went on it became increasingly clear that eyes cast down and periodical glances at phones were the new normal. A lot had changed, and students’ relationship with technology was no exception.

“So Ihde said he was gonna start taking phones,” Holloway said, “and people were annoyed, to say the least. Especially the people who weren’t in leadership before the pandemic, because that was their new normal. Well, that was their normal, not even their new normal.”

This shift in attitude toward communication among teens is a widespread phenomenon that has been slowly increasing as technology progresses. However, when the pandemic hit, the process was accelerated. Phone and screen overuse has become more common in young people, amplifying the division between students during in-person interactions.

“The research is pretty sound on this,” Biology teacher Shana Hains said. “Your generation is more open to the world than any generation before you, and yet as much access as you have, you’re lonelier.”

As a teacher, Hains has watched the evolution of how teens interact with the world around them first hand. From a biological perspective, the correlation between excessive screen use and dysfunctional mind and body systems is significant.

“There’s so many variables with human behavior, but what [psychologists] are seeing is that absolute direct correlation between screen time and happiness,” Hains said.

Studying a topic as convoluted as mental health is difficult and has to be approached as “soft-science,” meaning a correlation-based approach, as opposed to a clear path to a conclusion with only a few variables in play. When studying the correlation between mental health and screen use, scientists and psychologists have to be aware of the myriad other factors besides screen usage that could affect someone’s state of mind.

So what kind of factors are looked at when studying loneliness caused by screen time?

First and foremost, exploring how extensive amounts of screen time affects underdeveloped neurological functions is important to understand how those effects show up as measurable symptoms. What exactly are the psychological effects of screens that are causing rates of unhappiness, loneliness, anxiety and depression to increase in young people?

Psychology teacher Kyle Hall explained that while forms of communication such as texting and social media may feel like a genuine connection, it’s stimulating a completely different part of the brain than it would in person. When humans interact with each other eye-to-eye, they’re activating their occipital lobe, which is responsible for processing visual information, to a higher degree than they would while staring at a phone. Not only that, but areas of the brain that process auditory information and physical touch aren’t being used when a conversation is over text, which ultimately makes virtual communication ineffective in fulfilling human want for interaction in the long run. Short-term gratification, however, is a different story.

“It’s releasing dopamine, which gets you addicted to your phone,” Hall explained, “so you get withdrawals from your phone, which doesn’t make you happy. You don’t get chemical withdrawals like that from just not seeing one of your friends.”

These chemical withdrawals, named by the American Psychiatric Association as a symptom of a theoretical new disorder called Internet Addiction Disorder (IAD), help perpetuate the mindset that life exists digitally, which in turn creates an environment in which people become stressed, afraid, or depressed when they are not consistently checking their phones.

“You feel like you have more access to the world because you do, more than ever before,” Hall said. “You can talk to somebody from across the world. Just facetime them and there you are. So it gives people this false sense of ‘but look! We have it at our fingertips, we can talk!’ Yes, you can, but human-to-human interaction is vastly different than over the phone, and you can’t mimic that.”

This cycle of digital withdrawal leading to loneliness and anxiety struggles may be the reason that, as Holloway described, “We’re not always as connected as we think we are, just because social media makes it seem like we’re a lot closer with people.”

What does screen overuse look like at West Albany?

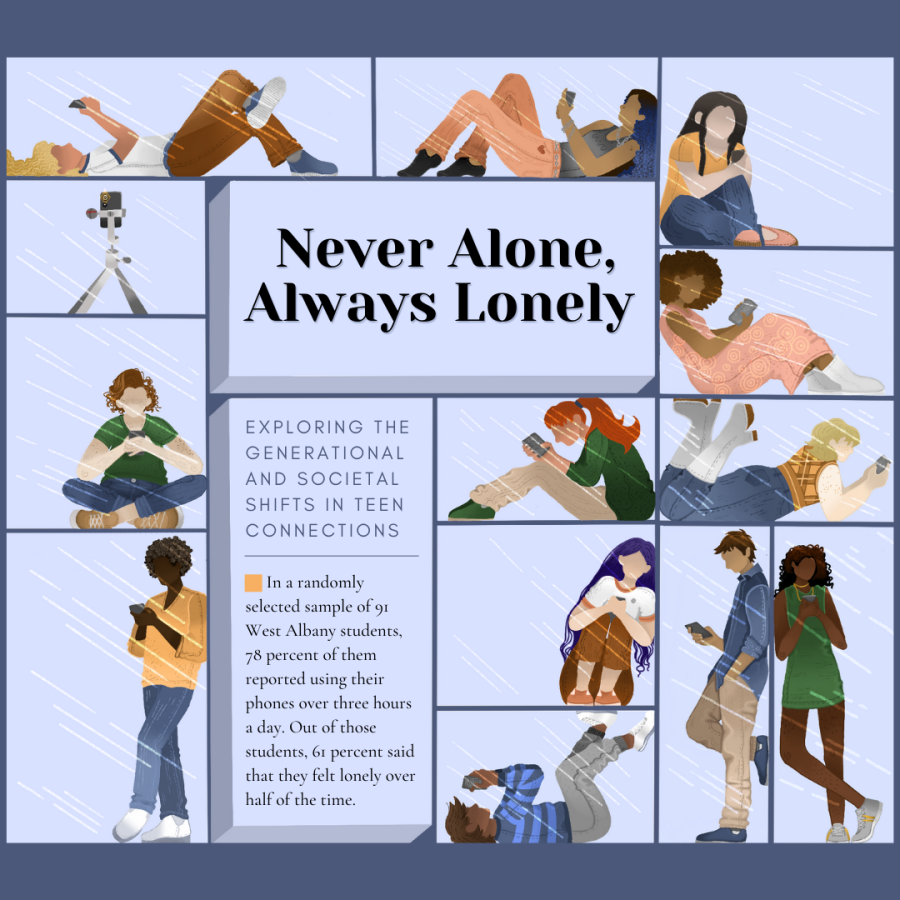

In a randomly selected sample of 91 West Albany students, 78 percent of them reported using their phones over three hours a day. Out of those students, 61 percent said that they felt lonely over half of the time. As reported screen time use increases, students experiencing loneliness remains above 50 percent. Out of the students that spend 12 hours or more on their phone every day, 88 percent feel lonely over half of the time.

Through her position as student body president and someone who has watched the school evolve since her freshman year, Holloway has noticed a difference in how people are socializing with their peers.

“Senior year you always hear that everyone comes together,” Holloway said. “Whether it’s in the movies, or even our parents or grandparents saying it, all the groups mesh together. I think I’ve seen that a little bit this year, but I feel like because of social media and the social group divide that it’s created, we haven’t seen that as much.”

Holloway speculated that the access to constant communication with friends that social media provides encourages students to stay secluded within a specific social scene. She’s noticed that people are more hesitant to reach out or even think about interacting with someone that is different from the group that they usually hang out with.

“Seeing the connectivity of everyone in our school, even just from freshman year to senior year, I’ve seen a decline,” Holloway said. “The social interactions just aren’t as much as they used to be in person.”

Yet even with social groups congregating online, Holloway explains, it can be difficult to fully connect with people that way.

“Social media friends are almost half there for you,” Holloway said. “You don’t always have those people that you can always count on, you have a lot of people that you can half count on.”

Hains also sees a connection between the willingness of students to step out of their comfort zone and their constant exposure to screens. Technology makes documentation easier, which means that all moments, the good and the bad, stick around for a long time. Increased levels of anxiety in anticipation that their embarrassing moments will be broadcast online may make kids much more hesitant to interact with the physical world around them.

“It makes you walk on eggshells,” Hains said, “because if you make a mistake, it’s not something that’s going to be forgotten by the next day. Even if somebody else makes a mistake bigger than yours, your mistake hangs around, and it’s thrown in your face. It’s just that fear that it might happen.”

This fear of embarrassment could apply to many aspects of student life. From Holloway’s perspective, social media combined with the potential for embarrassment has made it so that people no longer want to get involved with school events and activities.

“Whether it’s not wanting to go to a dance because you don’t have anyone to go with, I feel like social platforms have made it seem like you need to have a group of friends to go with or you’re going to look like a loser,” Holloway said. “It’s just created a sense of people not wanting to get involved.”

How does West Albany compare to national findings?

In an ongoing study done by psychologists at the University of Georgia and San Diego State University, research done with 1.1 million high school students found that “happiness levels were higher among adolescents using new media a few hours a week compared with those not using it at all, with mean happiness then progressively declining with more hours of use.”

West Albany students fit this trend to some degree, but not in all cases according to the survey of 91 students. Ninety-one students is about seven percent of the entire student body at West, and 1.1 million students is the same in comparison to the national population of high school students, seven percent.

The survey results from West Albany students found that students who spend zero to one hour on their phones all feel lonely less than half of the time. This is a stark contrast from the students who spend over 12 hours on their phone, of which 88 percent feel lonely most of the time. Rates of loneliness tend to increase as screen time increases, as shown in comparison to the national study in figure 1.

The differences are subtle, but the percentage of students who feel lonely over half the time is not a completely linear graph as phone use increases as reported in the UGA and SDSU study. However, over half of all students who spend more than three hours on their phones a day feel lonely the majority of the time. The steep incline at 10 to 11 hours to above 80 percent of students over three reporting feeling lonely over half the time shows a correlation between screen time and loneliness.

What are some possible solutions to helping students overcome digital dependency?

Recovering from the long-lasting effects of such a significant and addictive habit is not, and never will be, a simple feat. Addressing the root cause of teen unhappiness is not a straightforward solution; everyone has different factors contributing to their unhappiness. One thing is abundantly clear about digital dependence and screen overuse, though: society can never go back to how it was before technology.

“Am I hopeful? Yes, because I believe in science and I believe in education, and the more we can educate society about the problem, it’ll get fixed,” Hains said. “Do I think it’s gonna be too late for some? And already is? Yeah, I think the amount of anxiety and depression in our nation is terribly sad.”

Because the science and research on the subject is so new, it’s difficult to draw conclusions that will inspire national change.

“We live in a technological world where everything is being done digitally, so how do you fix that? I don’t know how you do it,” Hall said. “It’ll never be the same. So I think it’s up to us to adapt to the changing culture. Include technological advances but at the same time, do it in a way that’s safe and still allows us the time to promote interaction, promote things that are better for us than our phones or laptops.”