Psychologist famous for Stanford Prison Study Questioned

While under scrutiny, Psychologist famous for the Stanford Prison Study, Philip Zimbardo, addresses concerns the public has with the validity and ethics of the Study.

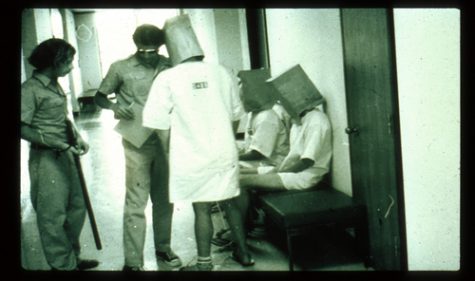

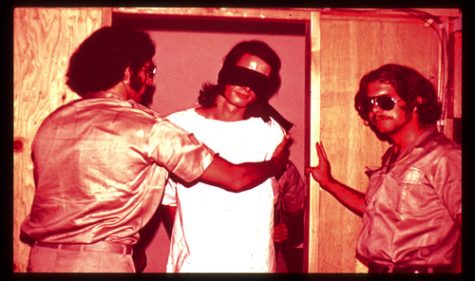

The Stanford Prison Study explored the idea of obedience and roles, especially when given certain roles to fulfill. 24 college students were randomly selected and given a role of either a “guard” or a “prisoner”. The study was originally supposed to last two weeks, but was ended after six days due to the hazardous conditions that were created. Those who were deemed guards took their jobs to an extreme and were abusive to the inmates, and the inmates became passive and took the abuse.

All of our psychology classes are elective classes. Throughout the course of the class, students study a variety of topics, one of which is the Stanford Prison Study. During this part of the curriculum, students are introduced into the basics of studying obedience and roles. With the Stanford Prison Study being so close to being discredited, it would be taken out of the classroom and students would be left wondering why they do certain things such as getting up when the bell rings, walking on the right side of the hall, or sitting in certain seats in class.

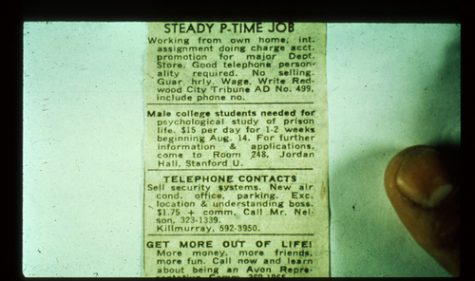

Until 1971, nobody had studied the idea of roles in humans, especially when they are given a specific role to fill. The Stanford Prison Study was developed by psychologist Philip Zimbardo in an attempt to promote himself while providing knowledge for other psychologists. However, within the past month, information has risen regarding the ethics surrounding the study. With the ethics in question, observers are attempting to discredit the study, and further, Zimbardo as a psychologist.

Philip Zimbardo began his career in psychology in 1954. Philip Zimbardo primarily studied and observed human behaviors. After the Stanford Prison Study concluded, he went on to study approximately seven characteristics within the realm of psychology due to reflections on the Study. In 2012, Philip Zimbardo was awarded the American Psychological Association Gold Medal for Lifetime Achievement in the Science of Psychology, and the presidency of the American Psychological Association. With his extensive background and knowledge of psychology, Zimbardo has proven himself to be a credible psychologist and has earned his credibility.

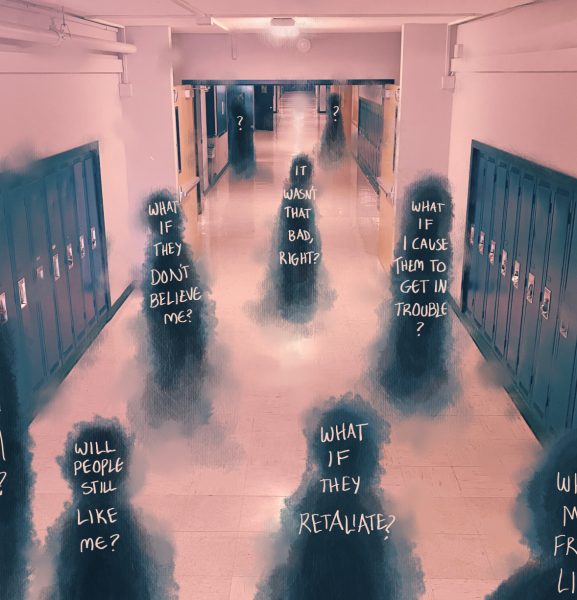

The Six Criticisms Zimbardo Faces

-

An unnamed staff member denounced the Stanford Prison Study as flawed and dishonest

-

The staff’s instructions for guards to be “tough” biased the guards’ behavior and distorted the outcomes

-

One guard was excessively like a guard in order to fit his role

-

There was a prisoner that faked a breakdown in order to leave the study early

-

A British research team failed to replicate the Stanford Prison Study

-

and why early publications appeared outside peer-reviewed journals to avoid rejection.

The Stanford Prison Study is Flawed and Dishonest

To begin, Zimbardo focused on a staff member, named Carlo, denounced the study as flawed and dishonest. Zimbardo responded on his website, PrisonExp.org, with, “The reality is that Carlo never wrote a word of that op-ed. He and I had become friends after our first meeting in my social psychology class in May 1971, and after I learned that he had served time in prison, I invited him to serve as SPE’s expert adviser on prison life. A careful reading of the student newspaper op-ed makes evident that the writer had a very distinctive legalistic style and vocabulary, not at all like Carlo’s. It turns out that its real author, who also published many related negative SPE comments online, was Michael Lazarou” (8-9). Zimbardo claims that when Lazarou wasn’t given the movie rights to the Stanford Prison Study, he began criticizing the work that was published by the producer, Brent Emery. Emery has phone records of Carlo explaining the comments attached to him were false and came entirely from Lazarou in May of 2005. With this cleared, the only criticism to be filed here was miscommunication and false accusations.

PrisonExp.org

“Tough” Guards Distorted the Outcomes

Secondly, Zimbardo addressed the guards being told to act “tough,” which as a result, distorted the outcomes of the study. The Stanford Prison Study observed roles in people when they’re given a specific role to fill. Do they take their job to the extremes, like some prisons do? Will the guards become “tough” and extreme with their punishments? Will the inmates rebel or be submissive? These were key questions in the study which were examined and noted through the six days of the study.

When asked about the accusation of a biased party, Zimbardo countered with, “My instructions to the guards, as documented by recordings of the guard orientation, were that they could not hit the prisoners but could create feelings of boredom, frustration, fear, and, a sense of powerlessness—that is, we have total power of the situation, and they have none. We did not give any formal or detailed instructions about how to be an effective guard” (10). The guards assimilated to their roles because in their minds, they were genuine guards of a prison. Further in Zimbardo’s response, he said the guards took a while to take on their roles fully, but in order to obtain sound results, those advising the experiment suggested they become more active in the experiment.

The advisers did not, however, explicitly say to ‘act tough,’ but instead urged the guards to get involved. After this interview, the guards made an attempt to be more active in their roles with punishments such as confinement to an extremely small cupboard that could be found in a classroom. In an effort to not distort the results of the study, the advisers used vague terms such as “firm” to allow for an open interpretation of what the individuals assumed to be firm.

PrisonExp.org

Guard Over Exaggerated his Role

Next, according to “Quiet Rage,” the video produced about the Stanford Prison Experiment, Zimbardo faced an accusation of a guard “play-acting” his role. The guard in question is named David Eshelman. Eshelman was one of the guards that stepped up after the advisers inquired about the lack of activity. During the study, Eshelman was nicknamed “John Wayne” after the out-of-control, Wild West Cowboy because he wanted to step up to his job but had no idea how to act like a prison warden. So, after the study concluded, Eshelman disclosed his use of John Wayne as inspiration to be a natural guard. Over the duration of the study, “John Wayne,” became increasingly vicious with his torture methods on the inmates. On the fifth night of the study, Eshelman had become so brutal that the study was ended in the morning. He was known for forcing prisoners to sexually assault each other in various positions, purely for his own pleasure and pride. Eshelman’s embodiment of a prison guard was exactly what Zimbardo and his advisers were expecting to see in the participant’s behaviors. Eshelman had completely conformed into an extremist prison guard without being provoked into doing so by the advisers.

PrisonExp.org

Prisoned Faked a Mental Breakdown to Leave the Study

The next attack was on the claim of a faked mental breakdown. Ethically, even if the breakdown were faked, Zimbardo still had to assume the breakdown was real. Even though the prisoner that faked the breakdown, Doug Korpi, was released from the study, he has changed his story of what actually happened on numerous occasions. Aside from the personal gain of treating the prisoner with dignity, the prisoner named, Doug Korpi, has changed what actually happened on numerous occasions. In the documentary, Quiet Rage, Korpi goes on record saying, “his time as a prisoner was the most upsetting experience of his life” (7). Korpi also described the experience to be so extensive that he went on to be a prison psychologist. On other occasions, Korpi has said he genuinely lost his mind, he was trying to liberate and free other prisoners, and wanted to ensure his attendance in a Graduate Record Exam. Zimbardo was able to discredit this accusation because the source that provided the information, Korpi, was unreliable due to his everchanging recollection of events.

British Research Team Fails to Replicate the Study

Zimbardo then acknowledged and refuted the claim that an unknown British research team failed to replicate his findings after conducting their own version of the experiment. Within the realm of psychology, it is understood that no experiment will be perfectly replicated every time; there may be exceptionally close experiments, but none will be perfectly alike. Looking at the extra variable the British implemented into their experiment is key to understanding why it had the opposite effect of the Stanford Prison Experiment.

The British version of the experiment was broadcast in a four-part BBC-TV show in May of 2002. With the study being publicized, it allowed for more intervention by the advisers and camera crew. So, the time in the “prison” was limited.

While still refuting the validity of the British version of the experiment, Zimbardo claims, “These researchers frequently intervened, made regular public broadcasts into the prison facility, administered daily psychological assessments, arranged contests for the best prisoners to compete to become guards, and as in many ‘reality-TV’ shows, created daily ‘confessionals’ for participants to talk directly to the camera about their feelings,” (9). Broadcasting the events around the world degraded the scientific impact of the experiment and rendered its findings entirely useless when studying true roles.

Fear of Rejection

Zimbardo challenged whether or not he was avoiding being rejected by the psychological community by publicising early copies of the study. He claims that this is not the case. He disclosed that he published his findings in the “Naval Research Review” because the U.S. Naval Research Office gave Zimbardo permission to conduct this experiment. His next publication was in the “International Journal of Criminology and Penology” by invitation of the editor. Zimbardo also ensures that he did not publish his findings in the New York Times Magazine as a way to sidestep around peer reviews; he merely wanted to reach a large, national audience.

Given the amount of time, research, and general “hoops” Zimbardo needed to jump through to even consider conducting the Stanford Prison Study, he was legally and ethically allowed to follow through. With the regulations Zimbardo went through, such as getting permission from the U.S. Naval Office of Research, there are no grounds for the criticisms that were voiced. The majority of the criticisms fell into the category of miscommunications and were dejected, by Zimbardo himself, in order to maintain the study’s credibility and his own credibility. As a psychologist, Philip Zimbardo has been able to prove himself through his credentials, experiments, and responses to controversy as a knowledgeable and credible source in the psychological community.

Your donation will support the student journalists of West Albany High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.