The Marketwatch Game: How two financial algebra teachers turned stock market lessons into a competitive and interactive way to learn

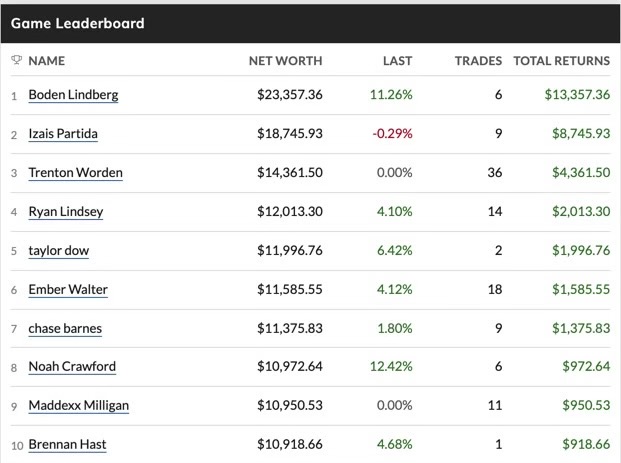

The Marketwatch game leaderboard during the first week of October

Investing in the stock market begins as a gamble. Putting money into stocks in hopes of increasing your net worth can be risky. However, there’s so much more to investing than a simple game of guessing. There’s equations and calculations that investors need to know in order to make the most informed decisions that won’t cost them their income.

WAHS math teachers Cole Pouliot and Derek Duman are working to create an interactive learning environment in which students can satisfy their curiosities about the stock market while simultaneously participating in a competitive, low-stakes game in which they get to invest fake money in the real stock market.

On Friday, September 10, nearly all of West Albany’s 148 Financial Algebra students received an imaginary $10,000 and bought shares of their favorite companies that they would follow, sell, and buy more of in the coming months. At the end of the semester, the game will end, and there have been hints at a possible prize for the student with the highest net worth when that time comes.

The site that makes this a possibility is called Marketwatch, a stock exchange site where games can be set up for classes or groups of people that are learning about the stock market, but aren’t quite ready for the real thing. As the Financial Algebra students learn more about the stock market in class, they’ll be able to apply their knowledge to the game while competing with other students and watching their stocks rise and fall.

Holding onto first place for nearly three weeks now is senior Boden Lindberg, who took the advice of a friend and is now worth over $23,000 in fake Marketwatch wealth as of Friday, October 1.

Lindberg gives the credit of his newfound net worth to senior Autzen Perkins, who had informed Lindberg in the days leading up to the beginning of the game that Dutch Brothers, the popular Oregon-based coffee company, would be going public on Wednesday, September 15.

“The first day of the game, Autzen just randomly told me in the halls that Dutch Brothers was going public, he said they were launching their IPO,” Lindberg said. “The only reason I knew what an IPO was was because I’ve seen ‘Wolf of Wall Street’.”

While the rest of the Financial Algebra classes invested on Friday, Lindberg bided his time until he could invest all $10,000 in Dutch Brother’s stock. His theory that the stock price would skyrocket after it went public turned out to be right, and the price of Dutch Brother’s stock went up 62% the day after Lindberg purchased it. He immediately sold his stock after hearing about the new price, and he’s been in the lead ever since, gaining over $13,000 in Marketwatch money, putting him in first place, where he’s been ever since. The only regret Lindberg has is not listening to his gut and putting real money into the stock.

“I was actually going to invest [real] money into Dutch Brothers, and then I kind of second guessed myself,” Lindberg said, “then in Financial Algebra on opening day, Mr. Pouliot tells us that Dutch Brothers went up 62%. My first thought was ‘oh my god I should have invested real money’.”

With all the buzz and competition around Marketwatch, students have been repeatedly checking their faux accounts, diversifying their portfolios, and discussing strategies outside of class. Pouliot is pleased with how well the game has been received, and he sees academic potential in the opportunity for students to interact with the market.

“I think they’re learning more and learning faster because of the game than if I just taught them how it is,” Pouliot said. “They’re asking how things work, and instead of just me teaching it, now they’re more incentivized to learn on their own. And that’s kind of a better way of teaching anyways.”

The idea for the game originated in an entirely different school district. While Pouliot and Duman discussed the curriculum for the year before school started, they decided they wanted more of an opportunity for students to participate in real-world investing without having to use their real-world money. Duman remembered an economics teacher at a school he worked at years ago who used an interactive stock market site as a way of teaching his students.

“Mr. Pouliot and I were talking about how kids are really interested in the stock market, and we thought ‘hey, how can we make that more applicable?’,” Duman said. “So I contacted my former colleague, and he gave us the name of the Marketwatch game, and that’s where I got the idea from.”

Duman knew that the stock market units were always popular among certain students, but he was surprised at the popularity of the Marketwatch game among a large number of students.

“Typically with this class when we talk about stocks there are some kids that are all in from the very beginning,” Duman said, “so we knew that there would be some kids that would be borderline obsessing over it, but I think the cool part is the number of kids that have been continuing to talk about it.”

The two math teachers recommend that if students are interested in real-world investing, they should research it more on their own, and start small so that they can get a feel for the market before investing large amounts of money. While neither teacher suggests coming to them for advice, they do encourage students who are seriously interested in trading stocks to look into hiring a financial advisor.

“We want to make sure that kids graduate and finish this class with an idea of how to manage their money responsibly,” Duman said. “We want to give them some tools that if they do want to invest or make money how they can do that in a way that’s been proven to be successful whether that’s through retirement or investing in the stock market and then kind of letting them hopefully go be prosperous individuals.”

Pouliot has similar goals, and hopes that students can use the Marketwatch game as a jumping off point.

“If it gets you interested then you can start to learn and eventually it can become something you understand at a higher level,” Pouliot said. “Hopefully it’s a stepping stone to a higher understanding of the stock market.”

Ultimately, the idea of the game was to produce a fun, interactive way for students to learn in their math class. Kids are talking with each other and having meaningful conversations surrounding the game, which Pouliot is delighted about after a year where it was so difficult for students to interact in a productive way with their classes through a screen.

“I’m just happy that the students are engaged in their learning and enjoying it. We’ve been gone for so long, it’s nice to have something that we can all talk about and enjoy. We’re having fun with math, we’re having fun with learning, and we’re having fun being together, and that’s what I really love about it.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of West Albany High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.