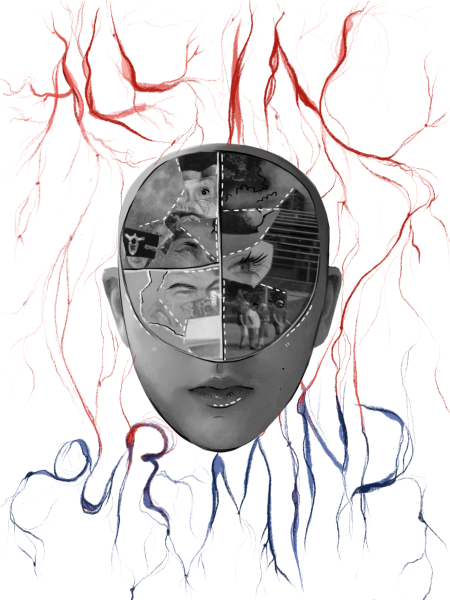

Play, Promote, Get Paid

A new law opens a wave of possibility for college athletes to commercialize their likeness for revenue

You walk by a student in the hallway wearing a steel gray Seattle Seahawks Russel Wilson jersey with a light gray three outlined in neon green. Another student passes, wearing a replica National Women’s Soccer player Alex Morgan jersey. But have you ever seen someone in a jersey worn by a college athlete? No, only by professional athletes. Well that’s prone to change.

On Jan. 1, 2023, Senate Bill No. 206 will be in effect, prohibiting California colleges from penalizing athletes if they advertise their name or likeness for payment. The National Collegiate Athletic Association, or NCAA, has told all colleges in the three divisions to consider updating their laws that previously banned such contracts in order to protect and maintain a balanced environment between students and the way they play. The new law, voted and approved unanimously on Sept. 30 this year, allows Californian athletes to promote businesses and products by using their name, uniform, and image to get paid.

The day when all colleges allow their athletes to get paid is a ways to come, for this decision will be a long process to finalize. But when asked whether or not he would do a contract like this when he gets in college, sophomore Autzen Perkins said, “Yeah, I’d sign up for it. I think it’s a good thing because as a young athlete that probably doesn’t know how to get their name out there [it’s important to] talk to these big organizations.” This Bill could be a new opportunity for student athletes, as the NCAA rules previously stated that no college athletes may be paid for advertising, no matter their division or scholarship.

Already colleges profit off athletes that attend their school as fans pay for tickets and other merchandise tied to the sports and events. The athletes work hard to play their best to support themselves in the game and at the university. The difference is that the athletes are not contracted with the businesses or booster clubs that support the athletes or sport, causing the athlete not to gain money, but they can gain audience appreciation.

This new law has intrigued some, but it also raises some questions. Health teacher and head football coach Brian Mehl brings up a good point: How are you going to pay the athletes equally? What factors would a college consider or even ignore when deciding who gets paid for what and why? For example, attempting to pay college athletes equal amounts for advertising regardless of what gender one identifies with may cause some issues seeing as the pay gap in professional sports is already extremely unbalanced. Mehl was a five-year football player, remarking that Division Three athletes play the game because they loved the sport and it wasn’t for any advantages in popularity or because you might get money along with it.

“If you’re on a team and you’re getting paid a lot of money, but your teammate isn’t getting paid any money at all, is that fair?” Athletic Director Patrick Richards asks. “Any sport, especially team sports, it takes more than just one person to be successful.” A team is not just comprised of one specific role for everyone, or one person doing everyone else’s job. There is structure, communication, and teammates who have each other’s back. But there are also hardships.

“I thought it was cool,” Perkins said, “because sometimes people struggle in life and money is part of their struggle.” Business contracts may put a strain on team dynamics, but for college students, who may not have any other source of income besides a possible scholarship or part-time job, advertising is a viable option for athletes.

If some colleges didn’t offer the athletes to contract with businesses, that could change a person’s perspective towards attending a certain school simply because the law wasn’t allowed for student athletes. Giving the privilege to advertise is up to the state governor and college Chancellor, but competing with other colleges that have passed the law may prove difficult. Especially when universities are trying to recruit athletes for their teams.

“I think a lot of colleges won’t [consider this law] because they don’t want their players to be part of something that could actually be negative,” Perkins said. The law won’t be in effect for three more years, specifically so that colleges and states have time to decide and rewrite their bylaws if necessary to adjust and make up their minds on this new upcoming change. Whether or not college athletes are given the opportunity to get paid for their likeness nationwide is still up for debate.

“We’re opening up Pandora’s Box,” said Mehl, “For every person that says work is fair, you’ll find two people that say it’s foul. There’s a lot of issues from mascots, to gender to the finances of it, there’s a lot of gray area.”There is no right or wrong answer in this debate of college athletes getting paid, for every college athlete has their own situation and every state has their differences, so regardless of whether the law works well or not, it will not be the same nationwide. Nothing is for certain yet on how much the rules of the NCAA could change, for better, for worse, or for indifference.

Your donation will support the student journalists of West Albany High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.